…pivoted, and restarted development of his teaching at least 3 or 4 times, depending on how you keep score. Immediately after forming the intention to benefit all conditioned beings by teaching the Noble Path, he concluded;

“And what may be said to be subject to aging… illness… death… sorrow… defilement? Spouses & children… men & women slaves… goats & sheep… fowl & pigs… elephants, cattle, horses, & mares… gold & silver [2] are subject to aging… illness… death… sorrow… defilement. Subject to aging… illness… death… sorrow… defilement are these acquisitions, and one who is tied to them, infatuated with them, who has totally fallen for them, being subject to birth, seeks what is likewise subject to aging… illness… death… sorrow… defilement. This is ignoble search.”

So rejecting the household life, he went forth into the homeless life of a bhikkhu. That was the first pivot. Then he approached Alara Kalama:

“Having thus gone forth in search of what might be skillful, seeking the unexcelled state of sublime peace, I went to Alara Kalama and, on arrival, said to him: ‘Friend Kalama, I want to practice in this doctrine & discipline.’

“When this was said, he replied to me, ‘You may stay here, my friend. This doctrine is such that a wise person can soon enter & dwell in his own teacher’s knowledge, having realized it for himself through direct knowledge.’ It was not long before I quickly learned the doctrine. As far as mere lip-reciting & repetition, I could speak the words of knowledge, the words of the elders, and I could affirm that I knew & saw — I, along with others…

“‘The Dhamma I know is the Dhamma you know; the Dhamma you know is the Dhamma I know. As I am, so are you; as you are, so am I. Come friend, let us now lead this community together’.”

But the Buddha was not satisfied with Alara Kalama’s teaching and moved on to Uddaka Ramaputta. This was the second pivot.

“In search of what might be skillful, seeking the unexcelled state of sublime peace, I went to Uddaka Ramaputta and, on arrival, said to him: ‘Friend Uddaka, I want to practice in this doctrine & discipline.’

“When this was said, he replied to me, ‘You may stay here, my friend. This doctrine is such that a wise person can soon enter & dwell in his own teacher’s knowledge, having realized it for himself through direct knowledge.’

“It was not long before I quickly learned the doctrine. As far as mere lip-reciting & repetition, I could speak the words of knowledge, the words of the elders, and I could affirm that I knew & saw — I, along with others.

Finally the Buddha saw the limitations of Uddaka Ramaputta’s teaching and left him to perform severe austerities alone in the forest. This was the third pivot.

“In search of what might be skillful, seeking the unexcelled state of sublime peace, I wandered by stages in the Magadhan country and came to the military town of Uruvela. There I saw some delightful countryside, with an inspiring forest grove, a clear-flowing river with fine, delightful banks, and villages for alms-going on all sides. The thought occurred to me: ‘How delightful is this countryside, with its inspiring forest grove, clear-flowing river with fine, delightful banks, and villages for alms-going on all sides. This is just right for the exertion of a clansman intent on exertion.’ So I sat down right there, thinking, ‘This is just right for exertion’.”

But wracking austerities did not deliver the enlightenment the Buddha was seeking either. So, drawing on his childhood experiences of meditative pleasure in jhāna, he pivoted again:

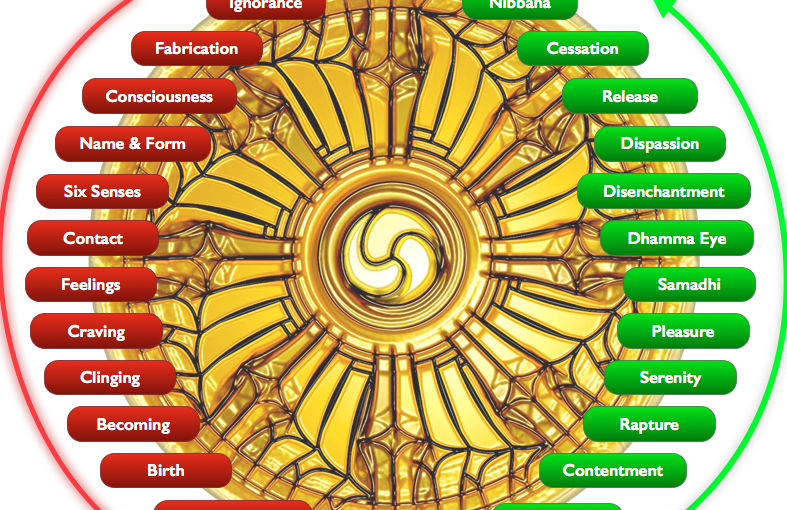

“Then, monks, being subject myself to birth, seeing the drawbacks of birth, seeking the unborn, unexcelled rest from the yoke, Unbinding, I reached the unborn, unexcelled rest from the yoke: Unbinding. Being subject myself to aging… illness… death… sorrow… defilement, seeing the drawbacks of aging… illness… death… sorrow… defilement, seeking the aging-less, illness-less, deathless, sorrow-less, unexcelled rest from the yoke, Unbinding, I reached the aging-less, illness-less, deathless, sorrow-less, unexcelled rest from the yoke: Unbinding. Knowledge & vision arose in me: ‘Unprovoked is my release. This is the last birth. There is now no further becoming.’

“Then the thought occurred to me, ‘This Dhamma that I have attained is deep, hard to see, hard to realize, peaceful, refined, beyond the scope of conjecture, subtle, to-be-experienced by the wise. [3] But this generation delights in attachment, is excited by attachment, enjoys attachment. For a generation delighting in attachment, excited by attachment, enjoying attachment, this/that conditionality & dependent co-arising are hard to see. This state, too, is hard to see: the resolution of all fabrications, the relinquishment of all acquisitions, the ending of craving; dispassion; cessation; Unbinding. And if I were to teach the Dhamma and others would not understand me, that would be tiresome for me, troublesome for me.’

Then Brahmā appeared to him and begged him to teach for the welfare of the world. We could regard this as a sixth pivot:

Then, just as a strong man might extend his flexed arm or flex his extended arm, Brahma Sahampati disappeared from the Brahma-world and reappeared in front of me. Arranging his upper robe over one shoulder, he knelt down with his right knee on the ground, saluted me with his hands before his heart, and said to me: ‘Lord, let the Blessed One teach the Dhamma! Let the One-Well-Gone teach the Dhamma! There are beings with little dust in their eyes who are falling away because they do not hear the Dhamma. There will be those who will understand the Dhamma.’

“That is what Brahma Sahampati said. Having said that, he further said this:

‘In the past

there appeared among the Magadhans

an impure Dhamma

devised by the stained.

Throw open the door to the Deathless!

Let them hear the Dhamma

realized by the Stainless One!”” — All quotes from: Ariyapariyesana Sutta

So if even the Buddha himself had to pivot and reorient his search several times, then what about us? We know enough about innovation to understand that it rarely succeeds on the first try. Thomas Edison trying thousands of formulas for the incandescent light bulb comes to mind.

And developing something like a light bulb or other piece of technology is simple compared with attaining enlightenment. So if you fail, fall down, make mistakes, switch methods, switch teachers, switch ontologies, you are in good company: the Buddha himself also pivoted several times before attaining his goal.

I’m always suspicious when some monk’s bio reads that he found his teacher at an early age and stayed on for years or decades, finally becoming his successor. It’s too neat; it doesn’t sound like the way it really is; it sounds like they were set up, and he whole thing was planned out. Made men in the monastery.

When I was first starting out I sampled so many spiritual teachers available on the US West Coast, both eastern and western. Most I rejected immediately; it was clear they faking it. I kept those with a clear disciplic succession (paramparā) who were faithful to their roots.

I joined several traditional organizations, large and small, Christian, Hindu, Budhist and so on; took the initiations, ordinations and empowerments they offered, and hung around long enough to find out what was really going on.

Sad to say, most were just money-making and power schemes. That doesn’t mean there were no intelligent, truthful, pure-minded people with deep knowledge and profound practice. But they were very much in the minority. I made it my business to make friends with them and keep in touch over the years, as part of my valuable spiritual inheritance and fortune.