“Monks, these two slander the Tathāgata. Which two? He who explains what was not said or spoken by the Tathāgata as said or spoken by the Tathāgata. And he who explains what was said or spoken by the Tathāgata as not said or spoken by the Tathāgata. These are two who slander the Tathāgata.” — Abhasita Sutta (AN 2.23)

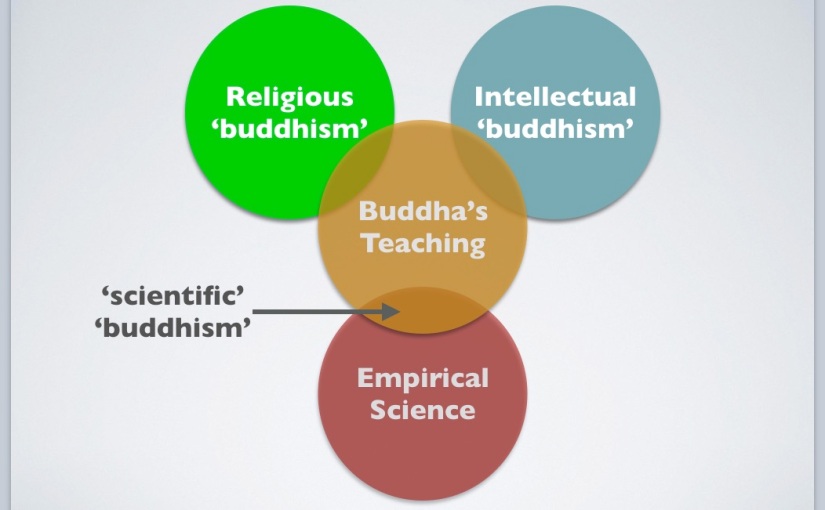

The Buddha compassionately brought light to the world, but that light is fading due to the covering influence of three very wrong concepts: religious ‘buddhism’, intellectual ‘buddhism’, and western ‘scientific’ ‘buddhism’. All three redefine the Buddha’s teaching in ways that he certainly did not intend and would not approve, and in the process cripple its self-transcending power.

Religious ‘buddhism’ is traditional Indian religion applied to the Buddha’s teaching. Similar offerings, hymns, statues and temples are built, but instead of Vedic deities like Indra, Rāma or Kṛṣṇa, the Buddha becomes the deity and object of worship. The Buddha never instructed anyone to build statues or other likenesses, worship them or make offerings to him after his parinibbāna (Unbinding). In fact, the core teaching of the Buddha is that everything that has being is impermanent. So, where is the Buddha? He is “Gone, gone, gone beyond, gone beyond beyond,” and never coming back into manifestation. Attaining that release is the whole point and goal of the Buddha’s teaching. So treating him as still present to receive offerings and prayers seems inconsistent.

Intellectual ‘buddhism’ is the idea that intellectual analysis and commentary on the Buddha’s teaching is sufficient to pass his legacy on to succeeding generations. My teacher Bhikkhu Ñāṇananda writes:

According to the Manorathapūraṇī commentary on the Aṅguttara-nikāya, there was a debate early in the Sri Lankan Sāsana between the scholar-monks and the meditators. And the conclusion was that merely communicating the words of the Suttas and commentaries would be sufficient for the continuity of the Sāsana, and that direct realization of the practice is not so important. So the basket (piṭaka) of the Buddha’s words came to be passed on from generation to generation in the dark — that is, without the corresponding realization.

As a result, later derivative works like the Abhidhamma and Commentaries increasingly displayed the ideas of their unrealized authors, rather than the Buddha’s deep insights. It led to degeneration of the practice and the Saṅgha as a whole, because of the idea that study alone was sufficient to realize the Dhamma. It’s not, and the proof is that very few people today become enlightened.

So-called ‘scientific’ ‘buddhism’ is neither scientific nor Buddhist. It is, rather, using empirical science as an excuse to reject vital aspects of the original teaching—such as karma, rebirth, and observance of precepts—that do not fit with contemporary notions.

All three of these deviations destroy the most essential and unique feature of the Buddha’s teaching: its power of self-transcendence. The self-transcendence of Nibbāna makes the Buddha’s teaching unique among all wisdom traditions. Without it, the Buddha’s teaching becomes yet another brittle set of beliefs, easily destroyed by changing conditions in the world. With it, the Buddha’s teaching is truly universal, ‘beyond the beyond’.

For, as Bhikkhu Ñānananda has kindly pointed out in his book Concept and Reality, Nibbāna is non-conceptual. To reduce it to a mere concept by defining it is to deprive the Buddha’s teaching of its most powerful aspect. Religious ‘buddhists’ have defined nibbāna differently than intellectual ‘buddhists’, but the effect in both cases is to deny their followers entrance into the Dhamma door of nibbāna.

Some may object by pointing out the list of 33 names of Nibbāna in the Saṃyutta Nikāya as definitions of Nibbāna. But if we examine them closely, we must conclude that these are not definitions but epithets or euphemisms: expressions that name the ineffable without defining it directly. This apophatic nature of Nibbāna is precisely the feature that gives the entire teaching of the Buddha its extraordinary power of self-transcendence.

An ontology is a set of terminology defined in terms of one another. Ontology and taxonomy are the semantic tools at the heart of all science. But any system in which terms are circularly defined is a closed system—brittle and subject to falsification. A single anomalous finding falsifies any theory.

But the Buddha’s teaching is applicable to any set of aggregates, for it is based on the cycle of being and becoming (paticca-samuppāda or Dependent Origination). It is incapable of falsification because any system of being and becoming, in this or any other universe, must be based on the principle of conditionality or causality. And Nibbāna, being the unconditioned, is never touched or affected by causality.